Music on the Pilot ACE Emulator.

Last updated: 15 July 2025

1. Contents

This document contains the following sections:

1. Contents.

2. Music on First Generation Computers.

3. Music on DEUCE.

4. Music on Pilot ACE.

5. Generating Individual Notes.

5.1 Six minor cycle loop.

5.2 Seven minor cycle loop.

5.3 Eight minor cycle loop.

5.4 Longer loops.

6. Structure of Program.

6.1 Stage 1.

6.2 Stage 2.

6.3 Stage 3.

7. Operating Instructions.

8. Example: Good King Wenceslas.

9. Appendix 1.

10. References.

2. Music on First Generation Computers

Many early computers had built-in speakers. They were used to alert the

operators when a program had failed or finished.

For example, the CSIRAC had a speaker (called the hooter), that was used to

signal the progress of a program. CSIRAC was the first Australian computer to be

built, and the fourth world-wide. "Programmers would place a sound at the

end of their program so they knew it had ended (this was known as a blurt)",

or they would place blurts in a program to indicate its progress.

The Manchester Mark II computer also had a loudspeaker and a special

instruction that stimulated it to emit a short pulse of sound.

It was soon realised that stimulating these loudspeakers at suitable

intervals would produce musical notes and that a program could string these

notes together to play a tune.

There is some dispute over who first wrote such a program. One claim is that

it was Christopher Strachey, in 1951 on the Manchester Mark2. Another is that

it was the mathematician Geoff Hill using CSIRAC, also in 1951. I am not

qualified to get into this argument but note ...

David Link quotes Martin Campbell-Kelly's report that

"Strachey sent his programme [draughts] for punching beforehand. The day came

and Strachey loaded his programme into the Mark I. After a couple of errors

were fixed, the programme ran straight through and finished by playing God Save

the King on the hooter (loudspeaker)." He also notes that "In a letter dated

15th May 1951, Strachey wrote to Turing: "I have completed my first effort at

the Draughts" and he was obviously talking about the Manchester Mark I.". So the

date of Strachey's first run must have been May or later.

"Hill programmed CSIRAC to play various popular tunes of the day, such as

Colonel Bogey, Girl with Flaxen Hair and so on. The music was one of

CSIRAC′s parlour tricks. Dick McGee remembers it playing music when he

started at the CSIRO in April 1951". Unfortunately, music played by CSIRAC

was not recorded at the time. "However, it has now been faithfully

reconstructed and can be heard again." The tunes are Colonel Bogey, The

Bonnie Banks o′ Loch Lomond and Auld Lang Syne.

[10.3]

The earliest recording of computer music that survives is on a 12-inch

single-sided acetate disc, cut during a BBC outside broadcast at the Manchester

laboratories, also in 1951. It captured three melodies played by the Manchester

Mark II, including the National Anthem and "an endearing, if rather brash,

rendition of the nursery rhyme Baa Baa Black Sheep as well as a reedy and wooden

performance of Glenn Miller′s famous hit In the Mood"

[10.1].

One can listen to the tunes in the article.

Over time, music programs became widespread. I personally recall visiting

an ICT (2nd generation) installation where the computer produced a convincing

imitation of someone whistling Colonel Bogey. The installation was a large room

full of cabinets and not all of it was visible at the same time. If you were

looking for someone it was a local joke for the operators to tell you he or she

was in the computer room, then turn on Colonel Bogey while you hunted around the

room and peered behind cabinets looking for the whistler.

Yet another example is SILLIAC, the University of Sydney computer built in

1956. On 17th May 1968, at its closing ceremony, SILLIAC played the Funeral

March by Chopin and Handel′s Dead March from Saul. It was then powered

down for the last time.

3. Music on DEUCE

DEUCE had a built-in speaker, but it worked differently. It could be switched

on using a program instruction (7-24 Alarm ON) but then stayed on until switched

off either by using another program instruction (6-24 Alarm OFF) or by manually

using a key on the facia. It was not suitable for producing music.

DEUCE could play music but to do so it required an external speaker. David

Leigh remembers singing along as their DEUCE played Xmas carols on Christmas Eve

[10.2]. Probably they were using John Denison's Melody

Maker described below.

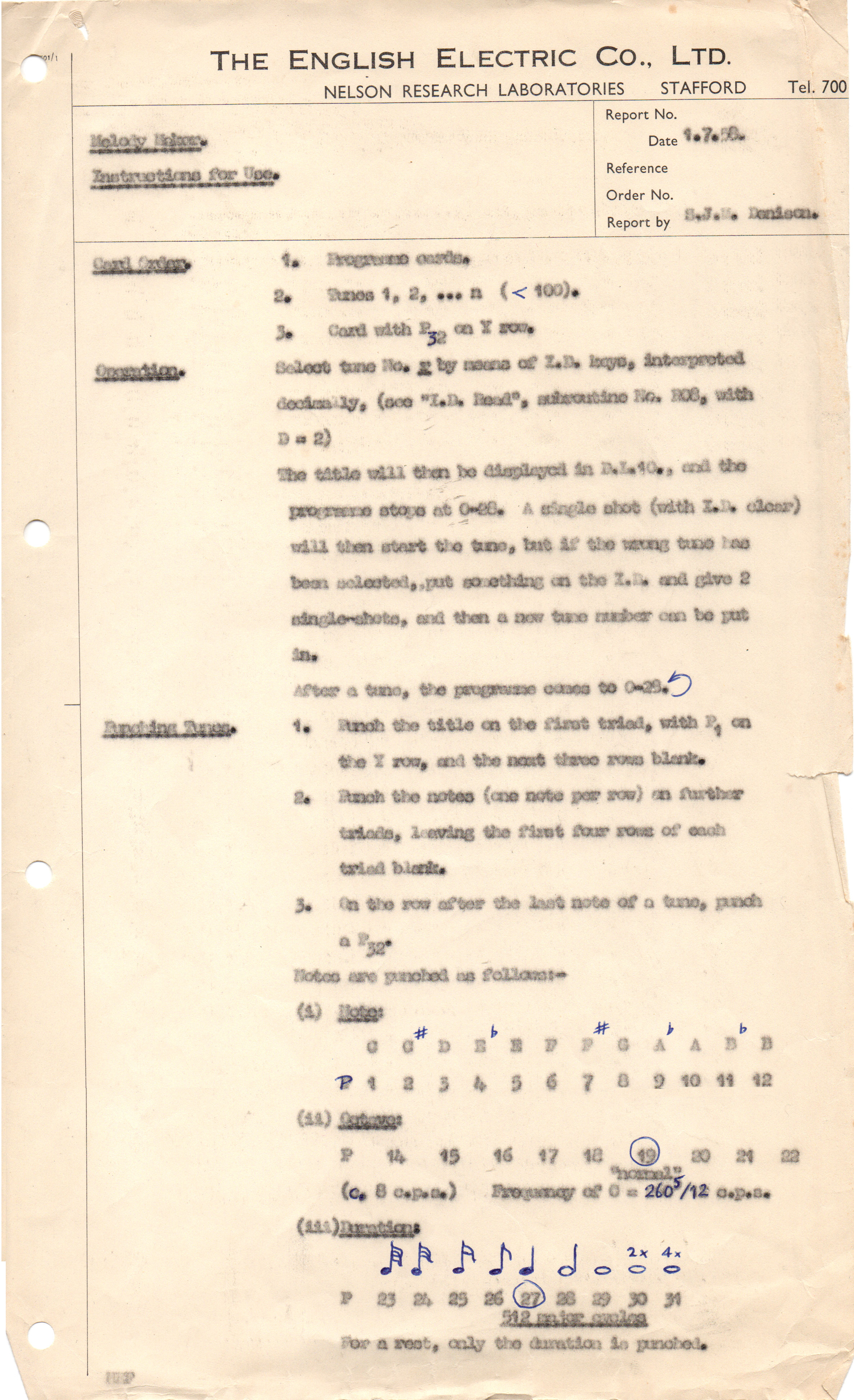

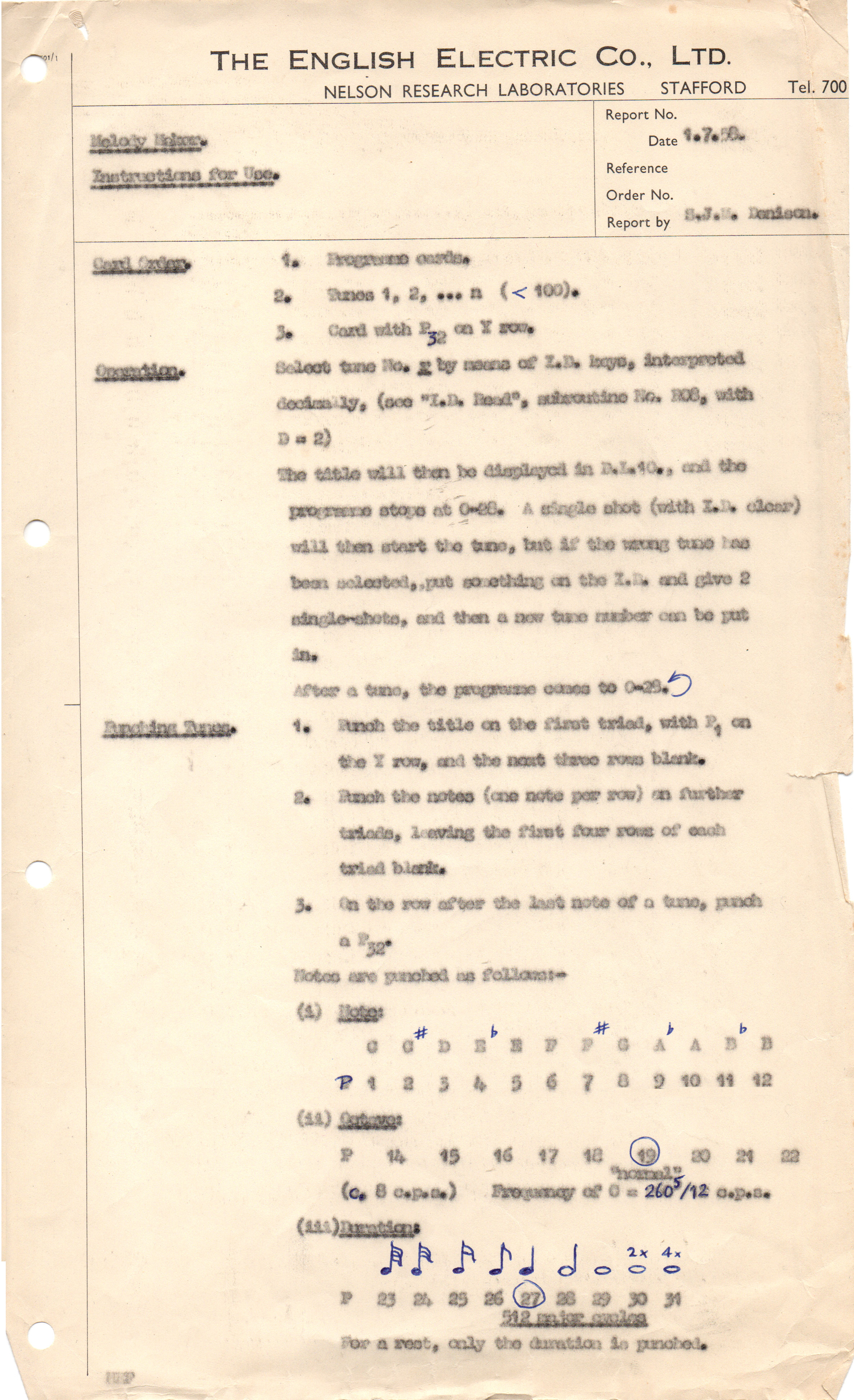

In 1958 John Denison circulated a program called Melody Maker to play music

on DEUCE. All that survives of the program is the first sheet of his write-up.

There are no flow charts, coding sheets or cards. Even this introduction is

probably missing a second page. Melody Maker allowed the computer to become a

sort of juke box, with coded tunes stored on the drum and available to be played

on request.

Melody Maker covered nine octaves, 108 notes from C0 to B8, far exceeding

the range of an 88-key piano (A0 to C8). It is possible that there were

caveats limiting the range, on a page now lost, but DEUCE could have produced

all of the notes under certain circumstances.

It might seem that the delay line structure of the DEUCE memory would prevent

the production of high notes (a minimum of 32 minor cycles required to repeat a

loop of code) but this is not so. There were ways to avoid this limitation on

DEUCE, and also on Pilot ACE.

There does not seem to have been a "standard" place to attach a

loudspeaker on DEUCE. It is likely the connection required for Melody Maker was

specified in a missing page of the operating instructions. David Leigh recalls

that at his DEUCE installation it was managed by stimulating the card punch

trigger, sampling the waveform that came out, and amplifying as necessary.

"This produced a square wave, of course, but we didn't exactly expect

Mantovani. 10-24 to turn the punch on, 9-24 to turn it off. (10-24 and 9-24 are

appropriate instructions.)" [10.2]. However, Robin

Vowels notes that on UTECOM (the DEUCE in Sydney) "Our Christmas carols

program didn't activate the reader or punch ... the speaker was attached to one

of the instruction staticisers.".

4. Music on Pilot ACE

I can find no mention in surviving Pilot ACE documents that Pilot ACE played

tunes. And John Parks, who helped maintain the Pilot ACE back in the day, told

me he had no recollection of hearing it play music. However, it undoubtedly

could have done, using an external speaker.

Pilot ACE had a built-in speaker (the buzzer). It could be switched on using a

program instruction (destination 29) but had to be switched off manually using a

key on the facia. It was not suitable for producing music.

Donald Davies, in "Very early computer music", recalled

that "The Ace Pilot Model [was] capable of composing music and playing it on a

little speaker built into the control desk. I say "composing" because no human

had any intentional part in choosing the notes. The music was very interesting,

though atonal, and began by playing rising arpeggios: these gradually became

more complex and faster [until they] dissolved into coloured noise as the

complexity went beyond human understanding."

"The origin of this phenomenon was a set of diagnostic devices put into the

machine by myself and David Clayden .. A cardinal feature of the machines .. was

"optimum programming" .. designed to make the utmost use of the (problematic)

access to data and instructions coming from the long delay .. So a measure of

programming quality would be the proportion of time that transfers were going

on. I thought that this could be measured very easily by smoothing a trigger

called Transtim. I had to remove the AC component from the signal to stop the

needle flickering too much, and it seemed logical to put this AC part into a

speaker just to hear what it sounded like."

"When the Ace Pilot model was due to move to a new location and become a

service, we thought that the crude old control panel should be replaced

by a nice new one. As soon as this new facility was working David

characteristically began to experiment with misusing it, and this is when

the music came forth."

He adds "The small meter on the control panel was a very crude measure but

the sound source naturally led to amateur compositions and the

customary transcripts of JS Bach." But he doesn't say when.

Duplicating John Denison's Melody Maker would serve no useful purpose now

but implementing music on the Pilot ACE is an interesting problem. The following

program shows one way in which it could have been done. Good King Wenceslas"

would have sounded something like this: